Nathan Smurthwaite On Lending Inspiration From the Everyday

Air Guitar, Purposeful Nonsense, and Lots of Nathans

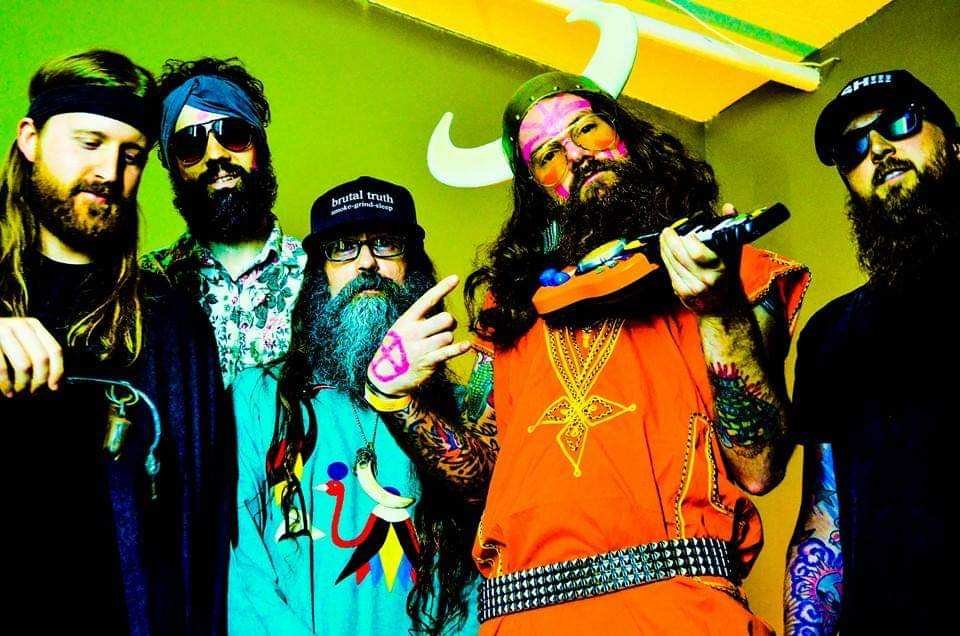

Nathan is not easy to pin down as an artist. He’s something of a shapeshifter in the music world—whether that entails hopping on somebody else’s project, jumping the gaps between genres, or fibbing on a new instrument until it produces a result passible for intentional playing, he finds a way to make it work.

At 10 years old, his parents gave him his first guitar (a mini acoustic Goya) and a year’s worth of lessons from a music shop down the street. But he credits the true inception of his musical career to the absence of the instrument altogether. “I started playing a lot of air guitar in the mirror because it was fun and made me feel cooler than I’d felt actually playing the guitar,” he tells me. All of that invisible, inaudible playing did him some favors, he thinks. “When I did come back to the guitar a few years later I was actually pretty nimble, and somehow it all just came naturally.” Soon thereafter, Nathan was playing a real guitar in Placid, his first of what would be many bands.

Nathan moved from Ontario, Canada to Washington when he was still in high school, and it was there that his second band, The Abadox, was formed. “We were faking it a lot at the beginning, emulating things we liked. It was very rough around the edges since we had pretty much no technical prowess. Lots of spastic noise.” In the early days, they added visuals to distract from—as Nathan put it—how bad they were. Which worked, by the way. Their go-to performance art required volunteers willing to wrap themselves head to toe in saran wrap (preferably red) and dance or crawl or really just stand there in the audience weirding people out. “In case you’ve ever wondered: it takes almost exactly one roll of saran wrap to dress a person from top to bottom and have everything covered.”

It was metal purely for the sake of a title, he tells me. Really it was a mishmash of heavy, experimental music with jazz stuff going on it. The goal was to fit as many different riffs as you could into one song, so the lyrics usually came second if they were considered at all. “The common theme in that band was nonsense. I actually kind of just made a bunch of babble noises and like, screamed. Which was sort of the joke.” Sometimes they would take things a little more seriously and make distinguishable words here and there, “whatever made me want to scream out at the top of my lungs.” Everything, he says, was about as tongue and cheek as it could get.

But The Abadox aged like a fine cheese; they only got better, more palatable, easier to digest over time. “Eventually we were actually as good as we’d thought we were when we first started playing. I felt like we could stand shoulder to shoulder with the bands we’d really liked growing up.” The difficult thing about a fine cheese though, is that once it’s reached its full potential, it has a tendency to disappear.” When Abadox broke up, I never really sorted out a way back to something that felt like that. We changed a lot over time, I learned a lot there. That band is always going to be up on a pedestal for me, in a way.”

After the band split up, Nathan and several former Abadox members forged on with the improv psych-rock group Fungal Abyss. Between then and now, he’s played with Seattle area bands and artists like Blacksmoker, Shannon Stevens, and Link Wray cover band Big City after Dark. For a while, Nathan also ran a Tacoma recording studio called Uptones where he engineered for numerous local acts. “It was tough though. I quickly realized that too much of a good thing becomes work.” He considers himself to be more of a bedroom-recording artist anyway; “I tend to fall into a scenario like this,” he says, gesturing to the small recording set up in a spare room of the machine shop he currently works in. “I find a small space or any that I can grab, and fill it with some gear.”

This is the ideal set-up for working on the solo project he calls Marrying Type. It’s a stark contrast to the psychedelic metalhead scene he’s usually affiliated with. In fact, with vocals reminiscent of Elliot Smith (who Nathan loves) and backing music similar to that of a folksy Syd Matters, it feels almost the opposite. The songs have a somehow beige and familiar texture, like the pages of an old book.

I’ve always played really extreme heavy metal, and then like, super soft, twangy, singer-songwriter music. Metal is only fun with other people, I think. It just makes a whole other thing happen that I’ve never been able to get to by myself with that style of music. The singer-songwriter stuff kind of saves me in that way; it gives me a place to make music by myself.

Plus, Marrying Type is like free therapy, he tells me, calling it his “sad bastard music.” “I think my muse was pain,” he laughs. A couple of songs might be about family, or Melanie (his wife), and love, or falling out of it. “But lately my muse, I guess, is music. It feels more like I’m writing to my musical career, for lack of a better way to put it. It sounds like I’m breaking up with somebody. I think it’s regurgitating some feeling about something that went good or bad about, sort of, my musical marriages. It’s only in hindsight that I realize I really am hung up on some things.” And not that I’ve done it myself, but I have to imagine that screaming artful nonsense into a crowd of people is also some form of therapy. Or at least that it is as cathartic as it might be exhilarating.

Despite his fluidity as a musician, Nathan still likes to keep the peas separate from the potatoes, so to speak. This is mainly true for Metal Nathan and Twangy Songwriter Nathan, who prefer not to cross paths. “When I was younger I didn’t care about what anybody thought at all, but somewhere along the line, I got a little insecure.” The Metal community, he explains, is definitively METAL.

In other words, nobody wants to hear your singer-songwriter set. And maybe they do, but it’s not what people say, you know. So sometimes I feel sort of secretive about it, even though for the longest time it was just a thing I did openly. I separated them into separate worlds, which in a way, maybe I shouldn’t have. These days, it’s almost like every project sits in its own little world, and really, more and more I don’t want them to cross over. I wish I could just be like 6 people instead.

General rules of existence prohibit us (as far as I know) from being more than one person at a time, but in the musical sense of things, it feels as though Nathan has managed to come pretty close to transgressing that. Speaking of which, there’s another Nathan we haven’t quite gotten to yet—the Nathan writing songs with his kids.

For a long time, his recording studio was a spare room in his house. But eventually, that became the girls’ bedroom, pushing the studio to the laundry room. “Their room still has a PA system in it. So they’ve always been around all the knobs, gadgets, banjos, the big percussion box of odds and ends. If I saw them gravitating towards anything I’d just try to give them whatever they needed to get into it. Isla liked to hit things for a while, so I’d bought her bongos, for instance.” The bongos didn’t hold her attention very long. Soon he was giving the girls all kinds of activities to complete with different instruments, coaxing out the idea of them starting a family band together. Under the name Dreamlandings, they’ve written and recorded several songs together over the years. But now it seems the kids are heading in their own creative directions. “Not to romanticize all this, but I think the pandemic has allowed them to hyperfocus on creative outlets. It’s given us more time to slow down, and just be around each other.” In any case, Nathan doesn’t mind all that much if they stick with it or not. It’s more about giving them the opportunities to try.

Most often, we use art to communicate, whether it’s with the world or just with ourselves, whether we mean to or not. Music and the genres within it offer us unique languages to do that in. “It always blows me away,” Nathan says, “most people are just living in this realm of several chord changes that sound good to our ears, and it just blows me away that you can continuously use that tiny bit of information to keep making so many things that feel new. And so it’s hard not to be inspired.” These days, Nathan can lend inspiration from almost anything—from new music to old heartbreaks to the evil bits of text haunting old YouTube comment sections. “I just want to build something in the way a kid would. I have this drum machine that I used to call my Gameboy,” he smiles. “For me, it’s like a video game—too easy to, or maybe, too hard not to keep going. Listening to other people’s music, just existing—I have to keep playing.”