Anthers: The Latest Wave, A Heart Attack

From left to right: Taylor Clark (drums), E.J. Tolentino (vocals/guitar), Kevin Blanquies (bass). Photo by Moni Martinez.

The loudest bands, I have found, are always the quietest in person.

The Cozy Nut Tavern in Greenwood is true to name; on a midsummer Tuesday evening the bar is sleepy, a scant few patrons conversing at a volume lower than the anodyne Spotify playlist eking out of the speakers. Taxidermied squirrels and horned sheep guard the premises. Everything is wood, the benches and tables warped by almost a decade of human weight and tenderly lit overhead by glass lamps. If you have superstitions, you could knock on any surface of the building and be safe.

The quiescence makes an interesting place of rendezvous for a band about to release one of the most cacophonous records of the year.

Pedigree Pig, the debut EP from fresh noise-rock trio Anthers, is a half an hour of atonal bombardments and thrilling bewilderment, like if a panic attack could feel good. From the moment “Mabel” blasts out of the speakers the band slam on the accelerator, refusing to ease up until the very last synchronous clicks of drum and bass. It’s clamor but not chaos; every element, from Taylor Clark’s pounding pentuplets on “Blow Mold” to the sinister rumble of Kevin Blanquies’s bass on “Tsuga,” represents three rigorous years of practice and fine-tuning. The EP is bound to catch ears near and far, introducing Anthers as a fully-formed act worthy of the hype it’s been steadily accruing.

Beforehand, Anthers spent the last year-and-a-half garnering that hype as incendiary live performers, wielding a svelte monster of a set for which earplugs are a necessity. The first time I saw them, at the Blue Moon Tavern during this year’s ‘Zoid festival, I remember getting slapped over the head with a sound check that nearly shattered the windows behind me. Via a fawn beige VOX amp, its logo quizzically flipped upside down, vocalist E.J. Tolentino wrapped his left hand around his guitar neck and wrung it like a sponge as a nearby box fan, in a futile attempt to cool the room, kept his hair in angelic motion. Out of his throat and into the standing microphone came the pained cry of some distant demon caught in penance for its sins, and the guitar turned into a searing-hot bident in its brimstone talons.

Afterward, he turned to the sound person and asked if the band could turn up a little louder. (He said no.)

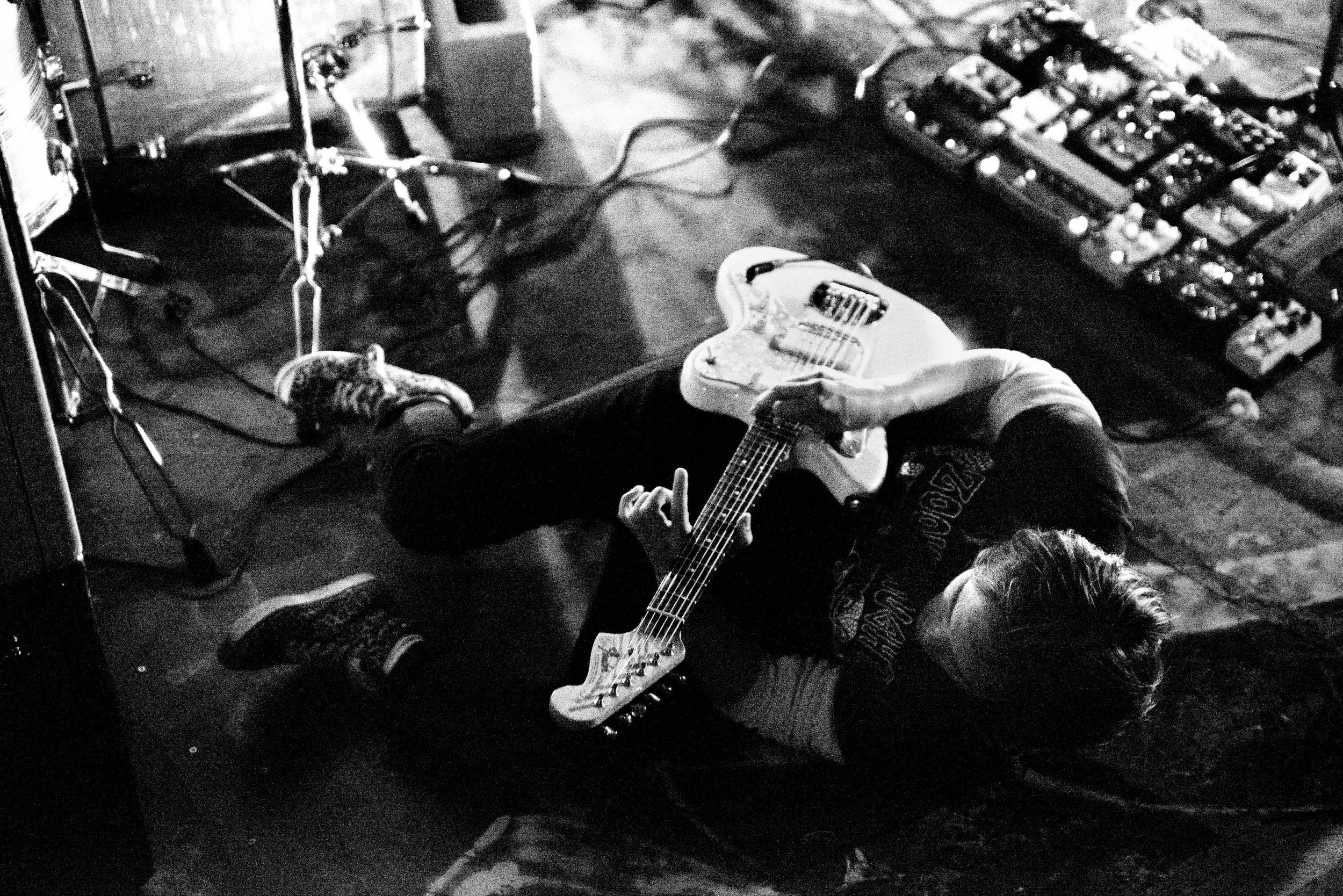

Photo by Sheri Foreman.

Sitting across from me in person, Tolentino is genial and gentle in his answers to my inquiries. At times he’s so soft-spoken that my transcription software can barely discern the audio. Next to him in the dimly-lit booth, the mustachioed Blanquies is similarly cordial as he polishes off something light and hoppy on tap. Beside me, Clark perpetually beams as he elaborates on his musical past and the ineffable chemistry between the band’s members. It could have been nerves or the drained bottle of Rainier emboldening me, but I fail to keep my observation of that contrast in dynamics to myself.

When I mention it, Tolentino, perhaps in politeness, agrees. “It's the people that play the quiet, peaceful music that you have to look out for,” he jokes. “Those are the wild ones.”

Tolentino is the only one of the three with roots in the area, having grown up on the Kitsap Peninsula and catching touring bands at the Showbox in his teens. One particular night, at Studio Seven to see The Darkness with friends, sticks out. “That night felt like a scene out of a movie,” he reminisces. “You know, the kind where a bunch of stupid teen boys borrow one of their parents’ vans and make the trek over. I think the car broke down at one point.” Later those same teens, by chance, met the band, and he kept one of the drummer’s drumsticks as a souvenir.

In the early 2010s, Tolentino founded CHARMS alongside Ray McCoy and Josh McCormick. The trio’s earliest efforts, mostly in the vein of the era’s indie rock, have been successfully scrubbed from the Internet. (You can, however, view a live session from 2013 that makes you question why they’d hide it all.) Instead CHARMS’ fashioned themselves into, in retrospect, a precursor to what Anthers would become: Tolentino’s trademark mixture of clanging guitar work and low-mixed doomsaying counterbalanced by McCoy’s tight drumming and McCormick’s piercing synths.

Those (including me) who were not a part of Seattle’s music scene during that time would be unaware of CHARMS’ omnipresence. They played everywhere, earned steady coverage from most every existing publication, and accrued plenty of fans – including KEXP DJ Troy Nelson, who helped sign them to Killroom Records. Those fans also included Clark, a native of Salt Lake City who was also building his own reputation as a drummer in GREAT SPIDERS. “Every time I'd go see a CHARMS show I'd be super excited about it,” he says. “But I’d also be a little bit envious. I just felt like...God, this makes sense. I could see myself doing something like this.”

E.J. or Kevin will have an idea that they'll "drum speak" to me…I love when that happens."

-Taylor Clark on Anthers’ creative process

Photo by Sheri Foreman.

Another fan, even more fatefully, was Blanquies. After moving to Seattle from Oakland in early 2014, he attended a show at Everyday Music at the behest of audio engineer Aaron Schroeder. CHARMS was on the bill, and Blanquies found himself extremely impressed by the band. Later, drinking with Schroeder at a bar, Tolentino walked in and a drunken conversation broke out. “I was living at my friend's parents' house while they were snowbirding in Florida,” says Blanquies. “It just so happened there was a room available at the house that E.J. was living in, and through a lot of maneuvering I was able to get in there.”

Part of what originally excited Tolentino about Blanquies, besides the normal excitement that comes from being very drunk, was his apparent skill at live visuals. “I asked him what he did creatively and he showed me all this amazing lighting and visual work,” he says. “I was like, you have to do this for my band.” Blanquies’ eventual set-up involved a projection of the band on a background screen that he would live-manipulate based on the band was playing. The effect was so successful that it became a critical factor of the band’s appearance, as integral to the experience as the sound. All three of CHARMS’ members would be immensely disappointed if Blanquies couldn’t make it to a gig.

Then, abruptly, CHARMS called it quits. 2017 hadn’t even ended; they’d released Human Error, their only surviving LP, back in June, and they’d played to a sold-out crowd at Reykjavik Calling that October. Suddenly Tolentino found himself without a band, and he stayed musically dormant over the next couple of years as he worked his job at a film archive . Eventually the itch needed to be scratched again, and Tolentino decided to start up another band alongside Blanquies. After running into Clark working at a Capitol Hill restaurant called Smith, he mentioned the project, and Clark’s previous interest was immediately piqued.

A series of unfortunate events, however, kept any hopes of a new band at bay. Tolentino fractured his elbow at a work party after a drunken encounter with a one-wheeler. (“It’s the opposite of what you think from a skateboard,” he offers sagely as he recounts crashing headlong into a lone A-frame.) Before he healed, another job forced him to move down to California. Then came the COVID pandemic, which dislodged Tolentino from his new job and allowed him to move back.

A Seattle resident once more, Tolentino rekindled the project, roping both Blanquies and Clark into the idea. “That was the best news ever,” says Clark. “I feel like my friendship with them really formed after we started playing music together. Now we see each other all the time.”

Anthers officially formed in July 2021, just over a year after the beginning of the COVID shutdown. Restrictions had just begun to lift, but as with all bands during the pandemic, existing quarantine protocols made it almost impossible to practice. “Even just feeling allergies or a hangover…” reminds Tolentino, “Every little thing was taken super super seriously, probably for the best. We would just cancel practice all the time, for any reason. We probably met a total of a couple weeks within the entire year because of COVID.”

Within those spare sessions, however, the band figured out how to write together. Specifically, they developed a process of collaboration where each member contributes their own parts while simultaneously translating the wills of the others. It slows down the process considerably - Pedigree Pig, at a mere seven tracks, features all but one of the band’s current songs - but it means that every member is happy with their contributions.

Clark’s drum playing is a good example: “Maybe more often than not, I'll kind of start with something, but then E.J. or Kevin will have an idea that they'll "drum speak" to me,” he explains. “That's my favorite thing, just trying to interpret that. I think it's cooler that way; it's like a little exercise, and it challenges me, and it's more fun. When a drum beat comes from somebody whose main instrument isn't drums, it's probably weirder. I love when that happens.”

Photo by KC Jonze.

“It’s kind of a thing where Taylor's translating what I'm saying, and then we retranslate it back and forth to each other,” adds Tolentino. “We're speaking different languages. But a lot of times what happens too is that I'll have this idea and I'll try to explain it to Taylor, and he'll make a drum beat that sounds kind of like what I was thinking, but it's actually better, 'cause I'm not a drummer. So I'm like, “...Yeah, that's what it was!”

If Anthers’ creative process is essentially one long game of Telephone, Blanquies’ grand role is translating ideas through his unique looking glass. Just like his latent gifts for visual art, Blanquies is also an adept at carving synth waves; right before our chat, he had clocked out from his job repairing synths. Even though he might be wielding a bass onstage, his ability to transmute that bass input into a thousand different shapes is a huge part of the package. “I have a pedal that can function like a modular synth,” he explains as an example. “You can build any sound you want. On ‘Gantuan’ there's the kick sound that's just modeled in there, and you can then make that interact with effects. It's a really fun way to mess around with sounds.”

Fun is one way to describe it - “awe-inspiring” is another. Nowhere is the band’s capacity for exploratory harsh sonics better represented than in Blanquies’ malleable bass work. Paired with Tolentino’s guitar manipulation, it arguably defines the band. It’s the very first thing you hear as Pedigree Pig opens, that low thrum striking each quarter note in a migraine of anticipatory dread. It’s still there when the track suddenly cuts to Tolentino’s hushed whisper and Clark’s ticking hi-hats, but it’s shifted into pure texture, a nauseous wave that ebbs and flows over the ears. Soon after, as the track reveals an inferno where a chorus should be, his bass becomes impossibly heavy, screeching and scraping across the ground like landing gear. And that’s just one song - there’s the aforementioned “kick” on “Gantuan” that’s more like a fetal heartbeat embedded in the walls, and the nightmarish low-end swallowing Clark’s drums on “UGGO.”

Photo by Moni Martinez.

Impressively, most of the sounds on Pedigree Pig are courtesy of the band’s playing - the record, engineered by the legendary Dylan Wall at Seven Hills Studio and mastered by the equally-lauded Ed Brooks, features comparatively little post-production. “Almost all that is us,” says Tolentino. “I think that was kind of a big thing, because there's so much going on in the songs anyway that the main goal – I mean, I don't know if that's the main goal, but one of the goals – was to capture that.”

Wall, who is also a member of Clark’s songwriting project The Leak, had an intuitive sense of what the band needed to sound like. “It felt like from the get go that he got what we were going for,” concludes Blanquies. “It saved so much time. He knew how to capture sound so that…” he pauses, trying to find the right words, “...it sounded like it should. There’s probably a better way to say that.”

Anthers’ made their live debut in March 2023, on a bill opening for Wild Powwers with local support from Bad Optics. It had been years since any of its members had played a show, and they weren’t sure what to expect. “When we started out of COVID, nothing was happening,” recalls Tolentino. “There were no shows happening, there was no music scene. We didn't really know what was going on.”

Their performance, painstakingly rehearsed and well-choreographed from the years of practice, set the bar high. Backstage in the green room, Zookraught’s Sami Frederick (who was subbing in for one of Bad Optics’ guitarists) caught Anthers’ sound check through the walls and wondered how in the world they were making their sounds. When they discovered Blanquies’ warped bass setup, they immediately became an admirer.

It's a slower process…but it comes up with results that we're happy with.

-Kevin Blanquies on Anthers’ songwriting

Photo by Jimmy Humphryes.

They wouldn’t be the only one for long. As Anthers played across the greater Seattle area, they found themselves uplifted by the enthusiasm and encouragement of the scene. “It's not only really good, it's just so incredibly supportive,” attests Tolentino. “We're all coming out to each other's shows, which is a huge difference. It's not just saying it. We see all these awesome other musicians that we look up to, and we're like, you didn't have to come to this. You already came to the show last year or last week or last month.”

It turns out that when the fields are left fallow, it makes the soil fertile. Unbeknownst to the band, the enterprising artists and establishments that reshaped Seattle’s post-pandemic underground had fabricated an ideal landing strip for an act like Anthers. Youths itching to blow off steam from the dormant years of quarantine had set up a thriving network of non-traditional venues. For the music that reverberated around these living rooms, or rang out into the dusty night air, nothing mattered more than sheer acerbity and energy: the ability to give the physically-starved crowds a context for which they could slam their bodies into each other.

Photo by Moni Martinez.

Anthers music, fittingly, is nothing if not physical. Compare it with Tolentino’s old band: his preference for colorful melodies, along with McCormick’s synth work, made CHARMS a human voice wrapped in a misanthropic mechanical being, like the one in Harlan Ellison’s I Have No Mouth and I Must Scream. Perhaps they endeavored to reflect their environment. The story of Seattle in the 2010s is a dystopian novel featuring Amazon as its faceless antagonist. For many artists, the encroachment of the corporation on their territory was a topic of interest bordering on obsession. In a long piece on Human Error, writer Dusty Henry notably contextualized CHARMS’ newly-aggressive music in the shadow of the city’s transformation, describing the album as “the hum of a world overrun by machines, fighting for its humanity against overwhelming synthetic pressure.”

Years later, under a post-Amazon, post-truth, post-pandemic, post-genre regime, is it any surprise that Anthers goes even farther? The music snarls and twitches like a feral, cybernetic beast. Its components aren’t as easy to parse, and the surprise nature in which they present themselves provokes a more visceral response. There are melodies, but they take a backseat to the textures and the heft of the volume by which they’re delivered. The boundaries of the tracks are porous — they start and stop at will, and they transition into each other seamlessly. This effect is even more pronounced live, where the entirety of their repertoire is presented as a beguiling, mercurial colossus with few discernible places to applaud. It's as if, like the ambient microplastics wedged inside us, the band has absorbed the cold chrome around it, survived, and mutated from its influence. The components might be mechanical, but the band uses them to convey a distinct animalism, a force as confounding and dark-hearted as the human spirit itself.

I'm the only one that knows what I'm talking about. I enjoy being the only person that knows.

-EJ Tolentino on Anthers’ lyrics

Photo by Courtney Davis.

Maybe Tolentino has learned his lesson, but when I finally ask him about the band’s lyrics he’s cagey, unwilling to give anything away. “I’m the only one that knows what I'm talking about,” he says. “And I enjoy being the only person that knows.”

It’s like this: “After we play a show, people ask me, ‘How the hell does Kevin make this sound? What is happening, what's going on?’ And some people come up to me and they're like, ‘What is this song about? What are these lyrics about?’ It's just...you just gotta know.”

Blanquies interjects. “For what it's worth, I've seen the lyrics, and there's a lot of songs where I have no idea what they're about. They're really cool lyrics, and they're very compelling, but I have no idea what the song is about. If I need to know, I'll know, and if I don't, I won’t.”

I do need to know, I argue internally. It’s my job. But instead of prying for concrete meaning like the dead end it is, I pose a question near the end of our chat: why did he flip that VOX logo upside down on his amp at the ‘Zoid set? Was it meant to coincide with the confusion, to pair with the assault on the senses? Was it a tiny thoughtful grace note on top of how painfully they craft their music? Was it out of boredom? Was it for fun?

“It’s a mystery,” says Tolentino. The beer glass in front of him is empty, a residual ring of suds sticking to the rim. Then he adds, in a voice as quiet as everything he’s said before it: “I encourage everyone who reads this to try to figure out why.”

Photo by KC Jonze.

Pedigree Pig releases September 20, with a simultaneous cassette release via Den Tapes.